6 Traditional Arts in Japan That Are Still Alive Today!

The reason Japan’s traditional arts have endured for centuries is that they remain living practices: performed, taught, and reinterpreted, instead of being locked away in museums. They’re traditions you can still encounter on stages, in classrooms, or even in casual community settings.

Each has its own role: some were designed to entertain large audiences, others to cultivate focus and discipline in daily life. And together, they reveal how Japan has balanced continuity with change, and why cultural expression remains so central to its identity. In this post, we’ll look at six traditional arts, from Noh theater to the tea ceremony, that are still alive today.

1. Noh (能) – The Classical Masked Theater

Noh is a form of musical drama that emerged in the 14th century, making it one of the world’s oldest continually performed theater traditions. Patronized by the samurai and elite, it mixes Buddhist and Shinto themes with tales of spirits, gods, warriors, and human emotions. Characterized by slow movement, chanting, and masks, Noh focuses more on evoking emotion through symbolism and atmosphere. The stillness of the stage, stylized gestures, and haunting flutes and drums create a sense of ritual rather than spectacle.

But Noh has a counterpart: Kyōgen (狂言), performed as comic relief between Noh plays. Using satire, wordplay, and everyday scenarios, kyōgen balances Noh’s solemnity with humor, making the two inseparable in traditional programs.

The aesthetics of yūgen (mysterious beauty) and wabi-sabi (austere simplicity) in Noh have deeply influenced Japanese culture, and recognized for its value, Noh and kyōgen were inscribed on UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list in 2008. Today, around 80 theaters nationwide host both professional and amateur performances, including venues like the National Noh Theatre in Tokyo and the Kanze Noh Theater in Kyoto.

To reach new audiences, actors and scholars carefully experiment with modern elements, from virtual reality to adaptations of popular stories (one recent production based on Demon Slayer ran from 2022 until 2025 due to its popularity). More than 650 years since its birth, Noh remains a living heritage, passed from master to apprentice and shared with audiences through performances, workshops, and festivals in Japan and abroad.

2. Kabuki (歌舞伎) – Japan’s Spectacular Drama

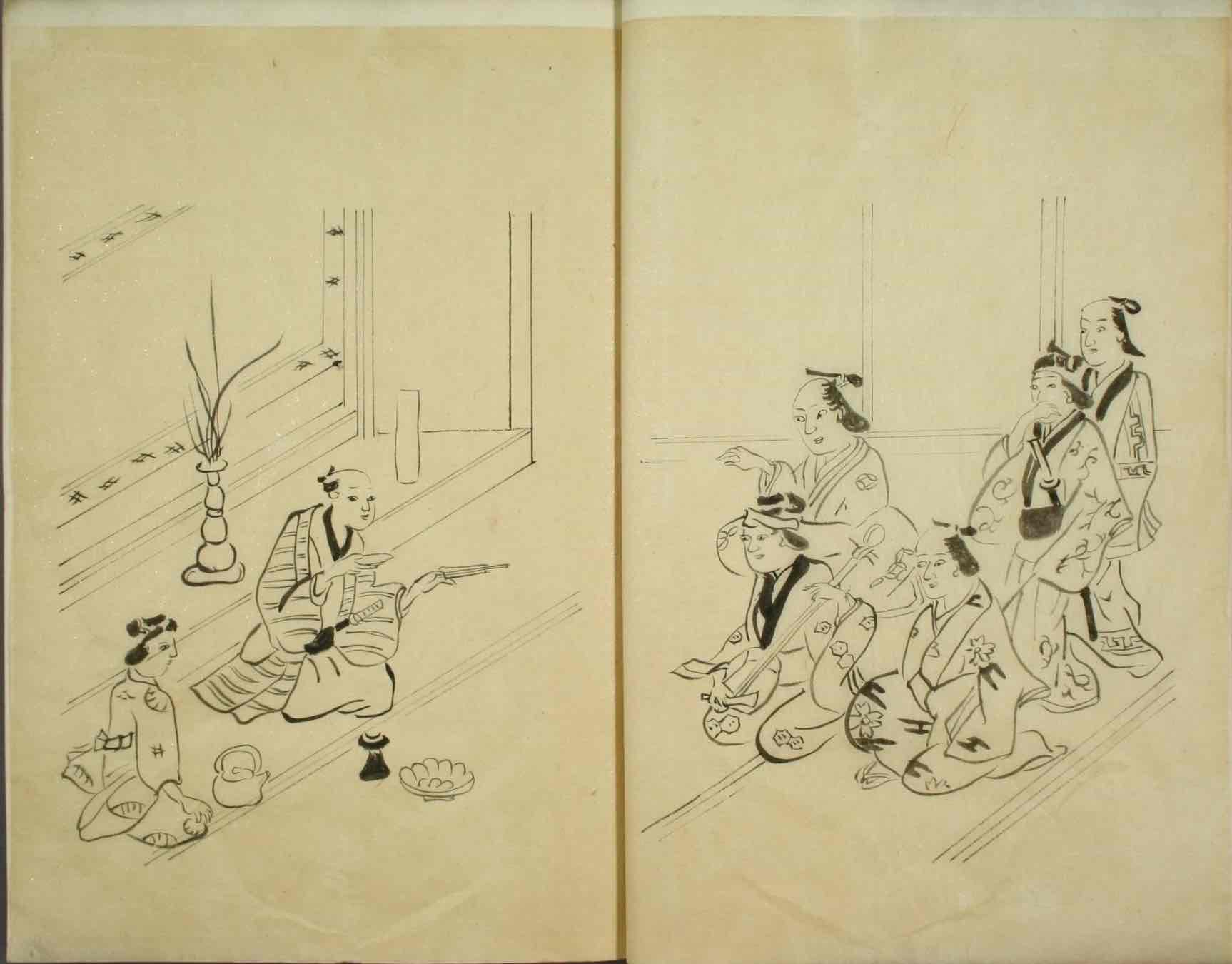

If Noh is subtle and restrained, kabuki is its bold, spectacular cousin. Emerging in the early 17th century, kabuki quickly became the theatre of the common people during the Edo period. Unlike Noh’s aristocratic roots, it flourished in bustling urban centers, attracting merchants, artisans, and townsfolk seeking lively entertainment.

Early kabuki featured female performers, but by the mid-1600s the shogunate banned women from the stage; ever since, all roles have been played by men, including the famed onnagata who specialize in female characters.

Kabuki is known for its colorful costumes, dramatic kumadori makeup, energetic movement, and elaborate stage effects. Plays range from historical epics of samurai and battles to domestic tales of love, duty, and betrayal, as well as dance-driven pieces with intricate choreography. Famous moments, called mie (見得), freeze the actor in a striking pose that heightens the drama of the scene.

Today, kabuki remains the most popular of Japan’s traditional theatre arts. Major venues like Tokyo’s Kabuki-za and Osaka’s Shochiku-za stage regular performances, often with adaptations that shorten plays for modern audiences. At the same time, kabuki continues to innovate: theaters use immersive projections and AR technology, while new productions adapt Western films or hit manga like One Piece and Naruto, drawing younger fans. Yet, despite these changes, kabuki’s music, dance, and stylized acting preserve the essence of its 400-year-old tradition.

3. Rakugo (落語) – The Art of Comic Storytelling

While Noh and kabuki rely on elaborate costumes and staging, rakugo strips storytelling down to its essentials: a performer, a cushion, a fan and a hand towel. Rakugo is a form of traditional comic storytelling that has kept Japanese audiences laughing since the Edo period (1603–1868). The name itself means “stories with a fall,” hinting at its punchline-driven style, and it's traditionally performed in dedicated theaters called yose as light entertainment.

A rakugoka (落語家, storyteller) sits in seiza position (Japanese traditional sitting) throughout the performance, using only voice, facial expressions, and minimal props to bring multiple characters to life. By simply shifting their head or tone of voice, they can switch between a samurai, a merchant, a child, or even a drunkard, all in the same scene, building up to a punchline (ochi or “fall”) told with clever wordplay and timing that delivers the laugh.

The stories usually mix the humor with a touch of popular wisdom, showing glimpses into ordinary life, relationships, and quirks of human behavior.

In modern times, rakugo has truly blossomed. In fact, the number of professional rakugo storytellers is at an all-time high, around 1,000 performers (the most since the Edo era), including about 55 women rakugoka who have recently entered what was once a male-dominated field.

These storytellers keep alive hundreds of classic tales while also creating new stories for contemporary audiences. And efforts are also being made to broaden rakugo’s reach beyond Japan. Notably, some performers deliver rakugo in English and other languages; for example, the late Katsura Shijaku II toured internationally with English rakugo shows, introducing global audiences to this 400-year-old storytelling tradition. Part of rakugo’s enduring charm lies in its intimacy. Unlike the grandeur of kabuki, rakugo feels personal, almost like sitting around with a witty friend who knows how to spin a tale.

4. Ikebana (生け花) – The Art of Flower Arrangement

Ikebana, literally “living flowers,” is the Japanese practice that elevates the act of arranging blossoms, branches, and stems into a disciplined art form. It began over 500 years ago with Buddhist monks making floral offerings, and by the 15th century the first formal school (Ikenobō) was established in Kyoto.

Learning ikebana was traditionally part of a refined education (especially for women of the samurai and merchant classes), and it came to be one of the three classical Japanese arts of refinement (alongside tea ceremony and calligraphy). It’s considered a way to cultivate patience and focus, as much a meditative practice as an art.

Unlike Western floral design, which often emphasizes fullness and color, ikebana focuses on minimalism, harmony, space, and respect for nature’s shapes. The placement of each stem is deliberate: a single branch might lean to one side to represent movement, while negative space suggests air and openness; practitioners focus on creating balance between the flowers, the container, and the surrounding empty space. Traditional styles often follow symbolic structures, with three main elements representing heaven, earth, and humanity.

Today there are over 3.000 different ikebana schools in Japan, each with its own philosophy and style, teaching the art to students young and old. These range from the traditional Ikenobō school, the oldest ikebana school, to modern schools like Sōgetsu, which encourage freestyle creative expression.

Ikebana is commonly practiced as a hobby and it’s also popular internationally, and in recent years, it has even embraced modern technology and new media to attract more enthusiasts. This continued existence of so many schools and the enthusiasm of practitioners worldwide show that ikebana, the art of letting flowers “speak,” is truly alive and blooming in modern times.

5. Shodō (書道) – Japanese Calligraphy

Shodō, meaning “the way of writing,” is one of Japan’s most respected traditional arts. It involves using brush and ink to write kanji (Chinese characters) and kana (syllabary) with style, rhythm, and spiritual focus.

Introduced from Chinese calligraphy around the 5th–6th century, the practice took on uniquely Japanese forms by the Heian period (794–1185), when hiragana and katakana syllabaries were created. Over the centuries, famous calligraphers like Ono no Michikaze elevated writing to an aesthetic pursuit, creating flowing, elegant scripts that were often used in poetry and literature.

What sets shodō apart is its focus on the act of writing as much as the result. The brush must move with precision and confidence, because once the ink touches the paper, there’s no erasing. This makes calligraphy a reflection of the writer’s state of mind (according to Zen philosophy): a shaky hand reveals hesitation, while smooth, bold strokes show focus and clarity.

Traditionally, shodō was a cornerstone of education (samurai were expected to be skilled in brush writing as well as swordsmanship), and it remains a respected art form used in everything from New Year’s decorative writing to temple inscriptions.

In contemporary Japan, calligraphy is one of the most commonly practiced traditional arts. Nearly all Japanese people are introduced to shodō in school, as it is taught during elementary and junior high. In recent years, shodō has also gained a cool factor among youth, partly thanks to the media. Popular manga, TV dramas, and even movies featuring calligraphy (for example, the anime Barakamon or the film Shodō Girls!) have sparked a revival of interest in the art among both young and old.

6. Tea Ceremony (茶道 / 茶の湯) – The Way of Tea

The Japanese tea ceremony, known as cha no yu (“hot water for tea”) or sadō/chadō (“the way of tea”), is one of Japan’s most iconic traditional arts. More than preparing and drinking tea, it is a choreographed ritual built on the principles of wa (和, harmony), kei (敬, respect), sei (清, purity), and jaku (寂, tranquility). Shaped in the 16th century by tea master Sen no Rikyū, its wabi-cha style emphasized simplicity and rustic elegance under Zen influence, values that still define it today.

For centuries, the tea ceremony was seen as an art of living for samurai and merchants, teaching mindfulness and refined manners.

In a typical gathering, a host prepares powdered green tea (matcha) for guests, following precise etiquette for every motion from cleaning the tea bowl to bowing to guests. The tearoom, scroll, and flower arrangement are arranged to reflect the season and encourage contemplation. The phrase ichi-go ichi-e (一期一会, “one time, one meeting”) captures its spirit: each tea gathering is a unique, once-in-a-lifetime moment to be cherished.

Today, the tea ceremony remains a vibrant practice preserved and shared with the world. While full training can take years, many enjoy it as a hobby through weekly classes, and tourist destinations like Kyoto and Tokyo offer simplified experiences for beginners. Modern adaptations, such as casual gatherings, make it more accessible while preserving its core values.

Preservation efforts are strong: the traditional tea schools Urasenke, Omotesenke, and Mushakōjisenke (the “three Sen houses” descended from Sen no Rikyū) continue to safeguard centuries-old practices, and tea utensils crafted by artisans remain highly valued. The grand masters of these lineages, especially Urasenke in Kyoto, have been recognized as key preservers of this important intangible cultural heritage. Thanks to their efforts, the tea ceremony endures in the 21st century as a living art.

Tradition in the Present

These six traditional arts are not static remnants of history; they are dynamic practices that continue to enrich Japanese life today. From the stage to the storytelling seat of a rakugo performer keeping Edo-era humor alive, from the quiet tokonoma alcove where a flower arrangement speaks of seasonality to the clatter of brushes at a calligraphy performance, and from the serene tearoom that offers a moment of reflection, each art form is being handed down and reimagined by dedicated practitioners.

In a rapidly changing world, Japan’s traditional arts provide continuity and a touchstone of cultural identity; yet they also show remarkable adaptability, proving that tradition and innovation can beautifully coexist. Experiencing these arts (in person or even online) offers a window into how Japan’s past lives on in its present, through timeless principles of beauty, humor, discipline, and harmony.

🍵 From Tradition to Your Own Journey

The same way Noh, kabuki, or the tea ceremony continue to evolve through each new generation of practitioners, your career path can take shape through experiences abroad! Internships in Japan are not only work placements: they’re opportunities to learn, adapt, and grow in a setting where tradition and modernity coexist every day. Join our program or reach out to begin your own chapter in Japan!