Workplace Diversity and Inclusion in Japan: Progress and Challenges

Diversity, inclusion, and accessibility (DIA) are gaining attention across Japan as companies and policymakers confront the realities of a changing workforce. A recent survey found that around 83% of Japanese companies believe that promoting diversity and inclusion, including recognizing same-sex and common-law partnerships, is increasingly necessary to attract and retain talent in today’s job market.

However, actual diversity metrics remain low: women hold only about 11% of management roles, the lowest in the region, and Japan ranks 118th on the Global Gender Gap Index. These gaps highlight a country in transition, where social expectations and business realities are beginning to clash, driving a slow but steady rethinking of what inclusion means in Japanese workplaces.

Current State of DIA in Japan

Japan’s progress toward diversity, inclusion, and accessibility has been gradual and uneven. In recent years, government initiatives and corporate pledges have pushed these topics into the mainstream, yet the reality on the ground reveals a complex picture. While there have been visible improvements (more women entering management, growing employment of people with disabilities, and a record number of foreign workers) the overall representation of minorities in Japan’s workforce remains limited compared to other developed nations.

Gender Representation

One of Japan’s most persistent workplace challenges continues to be gender disparity. Although women make up about 45% of the total workforce, their participation is often limited to non-regular or part-time employment, which accounts for roughly 53% of working women compared to just 22% of men. Another major concern is the gender pay gap, which remains among the widest in the OECD, with women earning only 75% of men’s wages on average.

While female labor participation has increased over the years, Japan still struggles with gender diversity in its workforce, particularly in leadership roles. As of 2025, women account for only about 11% of managers in Japanese companies, and over 40% of firms report having no women in management at all. At the executive level, women hold roughly 13–14% of director positions. To improve this, the government has set ambitious targets for listed companies on the Tokyo Stock Exchange’s Prime Market: 19% female representation in management by 2025 and 30% by 2030.

Disability Inclusion

On paper, Japan has a robust system to promote employment of people with disabilities. The government mandates a “statutory employment rate” (quota) for disabled workers, raised to 2.5% of a company’s workforce as of April 2024 (up from 2.3%). This policy has led to steady increases in the number of employees with disabilities, reaching a record high of 677,000 people in 2024 (about 2.4% of the workforce). Yet, these figures also reveal challenges: because the quota was raised, only 46% of companies now meet the legal requirement, down from about 50% a year earlier. In fact, nearly 60% of firms not meeting the quota employ zero people with disabilities.

LGBTQ+ and Other Inclusion Measures

Inclusion in Japan also varies across other dimensions. In recent years, there have been positive moves, such as more companies recognizing same-sex partnerships for internal benefits and a growing number of municipalities issuing partnership certificates for LGBTQ+ couples. Still, at the national level, Japan lacks a law banning discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity, leaving LGBTQ+ employees with limited protections.

This lack of safeguards is reflected in a 2024 survey by Robert Walters Japan that found that about half of LGBTQ+ workers in Japan reported experiencing discrimination in the workplace. Meanwhile, awareness of mental health and neurodiversity has only recently started to grow. Despite progress, these areas often remain stigmatized or misunderstood in many Japanese workplaces.

What the Barriers Are

A major factor is Japan’s traditional work culture and gender norms. Women in Japan can often experience what’s known as an “M-curve” career path: high participation in their 20s, a sharp drop in their 30s, and re-entry in their 40s or 50s. Many leave the workforce after having children due to limited support and persistent expectations that women should shoulder most family and caregiving responsibilities.

The shortage of affordable daycare and elder care options further limits opportunities for women to maintain full-time careers or advance into leadership; this has created a long-standing “pipeline problem” for female management roles. And in many companies, promotion practices still favor a homogeneous talent pool, where leadership is often given to men. Changing mindsets takes time, and the patriarchal norms continue to pose a psychological barrier for women pursuing careers.

Another key issue lies in Japan’s “compliance” mindset toward diversity. Many corporate D&I efforts are designed to satisfy legal or public expectations rather than create genuine inclusion. For instance, the government’s quota system for hiring people with disabilities pushes companies to meet numerical targets but does not guarantee disabled employees are actually integrated into organizations. Some firms hire just enough disabled employees to meet the quota, without ensuring equal access to training, advancement, or workplace support.

Similarly, when it comes to gender diversity, certain companies appoint a single female executive to their board to appear compliant with governance codes yet make few changes to the male-dominated corporate culture beneath the surface. These box-checking approaches can give the illusion of progress while leaving structural biases intact.

Legal and social frameworks also remain limited, and while Japan has anti-discrimination laws for gender (through the Equal Employment Opportunity Act) and disability, enforcement is inconsistent, and there is still no national law explicitly protecting sexual orientation or gender identity. This creates wide disparities in how companies address workplace equality.

Socially, open discussion about issues such as racism, sexual harassment, and LGBTQ+ inclusion remains relatively new, and progress has been gradual. Incidents like power or maternity harassment or subtle exclusion of those who “don’t fit the norm” have only recently started to be acknowledged. As a result, many minority employees still hesitate to express their identity or raise concerns, fearing isolation or subtle social pressure.

Altogether, these barriers reveal that inclusion in Japan is as much about cultural evolution as it is about policy. True change will require not just new policies but a cultural shift that values difference as a strength, not a disruption to harmony.

Progress, Innovations & Bright Spots

Despite the challenges, there are inspiring initiatives and gradual progress that shine a light on Japan’s potential for a more inclusive future. Companies, communities, and entrepreneurs are finding ways to make workplaces more diverse and accessible.

Corporate Initiatives

An increasing number of companies, especially multinationals and progressive Japanese firms, are investing in internal diversity programs. It’s now common to see employee resource groups or networks for women, LGBTQ+ staff or multicultural employees within large companies. For instance, companies like Shiseido and Toyota have women’s leadership programs, and many hold annual “Diversity Week” events to raise awareness. Some offices are being redesigned with accessibility in mind, with gender-neutral restrooms, nursing rooms for new mothers and wheelchair access. Another effort has been to support both parents in sharing childcare responsibilities, moving away from the expectation that it falls only on mothers.

A 2025 survey found that 77% of Japanese employers plan to continue or expand diversity initiatives, while only 3% were considering scaling them back. Such changes, while initially driven by a need to meet global standards, are slowly normalizing the idea that workplaces should adapt to employees’ needs, not the other way around.

Government & Policy Progress

The Japanese government has gradually expanded its efforts to promote diversity, inclusion, and accessibility across workplaces. In 2024, an important revision to the Act for Eliminating Discrimination against Persons with Disabilities came into effect, requiring all private businesses, not just public institutions, to provide “reasonable accommodation” for employees and clients with disabilities. This means companies are now legally obliged to make practical adjustments, such as modifying work environments or duties, to ensure equal opportunities and prevent discrimination.

At the same time, Japan’s national policy landscape is also gradually evolving to support inclusion more systematically. In June 2023, the LGBTQ+ Understanding Promotion Act (LGBT理解増進法) was passed, requiring national and local governments to promote understanding of sexual orientation and gender identity and to establish basic implementation plans. At the local level, Tokyo has also taken initiative by launching a portal site to help small and medium-sized businesses become more barrier-free and LGBT-friendly.

Changing Attitudes and Awareness

Perhaps the most encouraging bright spot is a generational shift in attitudes, with younger Japanese professionals being far more comfortable with diversity and vocal about inclusion than previous generations. Surveys show that millennial and Gen Z employees in Japan increasingly prefer companies that champion equality, flexibility, and value individual differences. This is pushing even small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in Japan to pay attention to D&I as a way to attract talent.

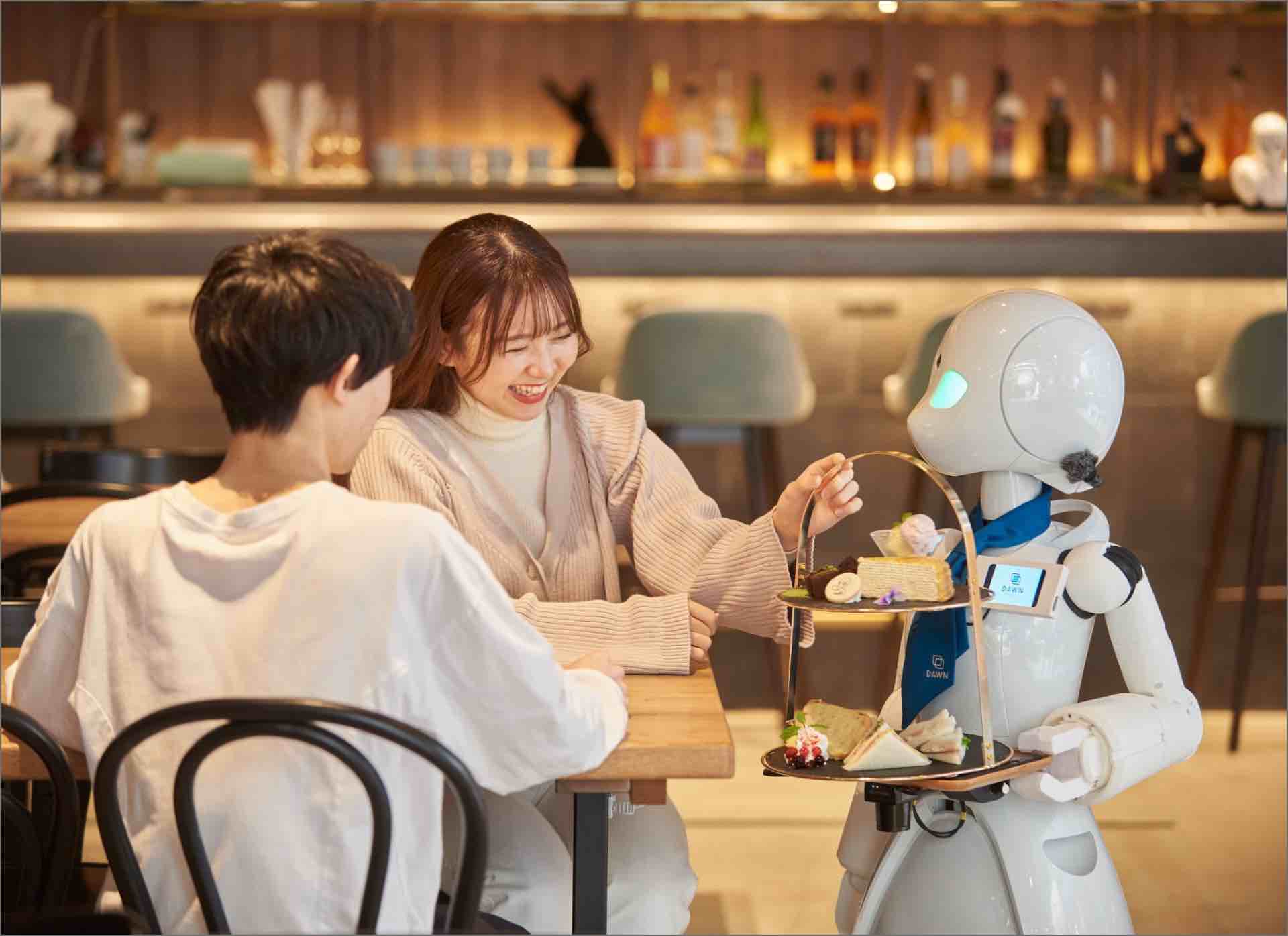

Success stories are also crucial: when companies embrace diversity and inclusion meaningfully, others begin to take notice, helping to reduce stigma around disability, LGBTQ+ issues or non-traditional career paths. One example of inclusive innovation includes Tokyo’s Avatar Robot Café DAWN, where people with severe physical disabilities work remotely as operators of robots serving customers. Or something more recent like silent cafés, where the staff is made up of deaf or hard-of-hearing people who interact with customers through gestures or written notes.

The Future of DIA in Japan’s Work Culture

Japan’s approach to diversity, inclusion, and accessibility (DIA) is expected to increase over the next decade, supported by government targets, shifting demographics, and changing attitudes across society and business. The government has set ambitious goals, such as ensuring that women hold 30% of leadership positions by 2030, alongside new requirements for large companies to disclose gender ratios and action plans for gender equity.

Efforts toward disability inclusion are also advancing, with the legal employment quota set to rise to 2.7% by 2026 and discussions already underway to increase it further in the coming years. At the same time, progress on social issues is also gaining traction: since the passage of the 2023 LGBT Understanding Promotion Act, both national and local governments have been tasked with promoting awareness and implementing inclusion measures, while some courts and municipalities continue to push for legal recognition of same-sex partnerships.

Within the corporate sphere, DIA is evolving beyond checklists into long-term cultural transformation, as companies are increasingly consolidating their gender, disability, LGBTQ+, and foreign talent initiatives under unified Diversity & Inclusion departments, showing a more integrated approach. This shift is supported by mentorship programs, leadership training, and flexible work systems such as flextime and remote work, designed to create environments where employees from different backgrounds can succeed. In parallel, as global ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) standards place greater importance on social impact, Japanese corporations are including diversity goals into their broader sustainability strategies.

Demographic and generational change will also drive this evolution; with a shrinking population, companies have little choice but to diversify their talent pools, by encouraging higher female participation (because female workforce participation still has room to grow) and welcoming more foreign and minority workers. By 2030, many new job seekers will have grown up in the Reiwa era, shaped by global and digital influences that foster openness and inclusion, and they are expected to prioritize employers that reflect those values, which will, in turn, push even conservative firms to adapt or risk losing talent.

Finally, international collaboration will also reinforce this direction: global companies operating in Japan are setting higher expectations for inclusivity. As Japan becomes ever more connected to global standards, diversity will be central to its competitiveness and future growth.

Toward a More Inclusive Future

Japan’s journey toward greater workplace diversity and inclusion is far from over, but the momentum is undeniable. Progress in policy, corporate culture, and public awareness shows a clear shift from compliance to genuine transformation. As aging demographics and labor shortages push organizations to rethink who makes up their workforce, inclusion is becoming an economic necessity as much as a social goal. The rise of inclusive innovation reflects a broader truth: embracing diversity strengthens creativity, productivity, and connection.

💫 Be Part of the Change

Japan’s workplaces are evolving, embracing new perspectives, people, and ideas. Taking part in an internship in Japan not only lets you experience that change up close but also be part of it! If this is something that excites you, then join our program or get in touch with us to start your journey toward interning, and growing, in Japan.