Japanese New Year Traditions, Part 2: The First Days of the Year

After the final preparations of late December, January 1 marks the start of a national holiday period when work pauses, daily routines ease, and focus turns to time spent resting at home.

This second part continues from the earlier look at how Japanese families prepare for the New Year, focusing on what happens once the year begins. It explores how New Year’s Day is spent at home, traditional meals, first shrine visits, seasonal travel, and how these practices have changed over time, showing how families across Japan mark the beginning of a new year.

4. New Year’s Day (元日)

Hatsuhinode (初日の出)

One enchanting New Year custom for those willing to wake up early on ganjitsu is hatsuhinode, the first sunrise of the year. Watching the sun rise on January 1 is believed to bring good fortune, health, and renewed energy for the year ahead. The custom ties closely to the idea of beginnings; the first light of the year marks a clean start, both spiritually and emotionally.

Many people will make the effort to get up before dawn (or stay up after midnight) and go to a good viewpoint, like the beach, a mountain, or an open hill to watch the sunrise in person. Popular spots include beaches facing east, observation decks, and elevated parks. Others choose a simpler way, watching the sunrise from a balcony, a nearby riverbank, or even on television, where live broadcasts show hatsuhinode from famous locations across the country.

As the sun’s rays spread, people make a wish or offer a prayer for health and happiness in the new year. Traditionally, this practice is also linked to welcoming Toshigami-sama, the New Year deity, since the first sunrise is thought to be when the deity arrives.

Day at Home and Osechi Ryōri

January 1st in Japan is typically spent at home, and things calm down compared to the days leading up to it. With most shops closed, families usually relax together, marking a clear pause after the busy end-of-year period.

Many households turn on the television early, as New Year programming plays a central role in the day, with comedy specials, music shows, and traditional broadcasts running throughout the day. Another common custom is drinking otoso (お屠蘇), a lightly spiced medicinal sake sipped on New Year’s morning to ward off illness and bring good health in the coming year.

Meals on New Year’s Day center on osechi ryōri (おせち料理), a collection of dishes prepared in advance and arranged in tiered lacquer boxes called jūbako (重箱). Preparing the food ahead of time means no cooking is required during the first days of the year, allowing everyone, especially those who usually handle meals, to rest.

Each osechi dish carries symbolic meaning tied to hopes for the year ahead: kuromame (黒豆, sweet black soybeans) represent health and diligence; kazunoko (数の子, herring roe) symbolizes prosperity and many descendants; and datemaki (伊達巻, a sweet rolled omelet) is associated with learning, its spiral shape resembling a scroll.

Other common items include kurikinton (栗きんとん, sweet potato and chestnut mash) for wealth, shrimp for long life, lotus root for clear vision into the future, dried sardines (田作り, tadukuri) for abundance, and red-and-white kamaboko for celebratory colors. The stacked jūbako boxes themselves are symbolic, with each layer said to multiply good fortune.

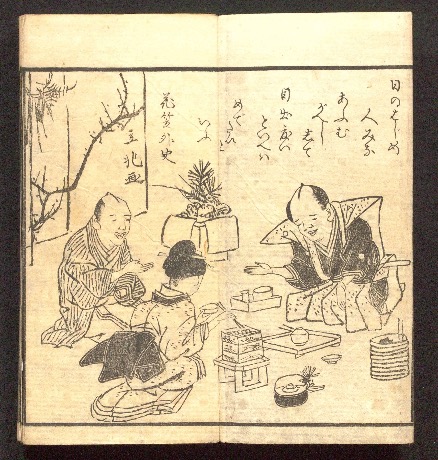

Osechi ryōri has ancient historical roots, tracing back to seasonal court rituals of the Nara (710–794) and Heian period (794–1185), when special foods were offered to the gods at key times of the year through banquets called osechi. New Year’s was the most important of these moments, and the associated dishes became increasingly elaborate. During the Edo period (1603–1868), the custom spread from the imperial court to ordinary households.

Cooking at the start of the year was once considered unlucky, as it could anger the fire deity, which is why osechi relies on preservation methods such as simmering, pickling, drying, or sweetening. Because the first meals of the year were believed to influence one’s luck, osechi became a collection of edible good omens, enjoyed from January 1 to 3 as families quietly welcome the year ahead.

Otoshidama (お年玉)

One of the most anticipated parts of New Year’s Day for children in Japan is otoshidama, the tradition of giving cash gifts to younger family members. Otoshidama is usually given by parents, grandparents, and sometimes close relatives, and the money is placed inside small decorative envelopes called pochibukuro (ポチ袋), which are often brightly decorated with animals, characters, or New Year motifs (like the zodiac animal of the year).

The amount given varies widely depending on age and family custom but generally increases as the child gets older. For example, a toddler or kindergartener might receive around ¥1,000 (roughly $10), elementary school children may get a bit more (¥3,000–5,000 is common), and teenagers could receive ¥5,000–10,000 (up to around $100) in each envelope.

There is no fixed rule, and adults adjust the gift according to what is seen as appropriate for the child’s stage of life. Usually, the bills should preferably be new, clean, and undamaged, rather than wrinkled notes taken from a wallet, as new bills symbolize a fresh start and proper preparation for the New Year.

Beyond the monetary aspect, otoshidama plays a role in teaching children about saving, gratitude, and family bonds, while also carrying the sentiment of wishing them good fortune and reward for the new year.

5. New Year Visits and Activities

Hatsumōde (初詣)

Between January 1st and 3rd, families across Japan visit a Shintō shrine or Buddhist temple for hatsumōde, the first shrine visit of the year. Some people go right after midnight on New Year’s Eve, while others visit later on January 1 or over the following days. Many choose less crowded dates, extending visits into the first week of January.

Major shrines and temples draw enormous crowds during this period. Sites such as Meiji Jingū in Tokyo or Fushimi Inari in Kyoto receive millions of visitors over three days. To manage the influx, shrines extend opening hours, set up food stalls selling warm snacks and amazake (甘酒, sweet sake), and organize long lines for worshippers.

The prayer routine is familiar: visitors throw a coin, often a five-yen piece, into the offering box, ring the suzu bell if present, bow twice, clap twice, pray silently for health and good fortune, and bow once more. Afterward, many draw omikuji (御神籤), paper fortunes; if the fortune is bad, it is tied at the shrine to leave misfortune behind. People also purchase new omamori (お守り) charms for the coming year and return old ones to be ritually burned to release their spirits.

Visiting a Buddhist temple is equally common, and some families do both, attending a temple bell ceremony on New Year’s Eve and visiting a shrine the next day. Hatsumōde is practiced nationwide, from small neighborhood shrines to major religious sites. It is also a family outing, one of the few times multiple generations might go to a shrine together. Parents, children, and sometimes grandparents go together, often taking the opportunity of the visit to also go for a walk, get street food, or meet relatives.

Family Visits and Travel

The New Year holiday is also an important time for family reunions. Many people travel back to their furusato (故郷, hometown) or to their grandparents’ house to spend January 1–3 with their extended family.

In fact, the end of December is one of Japan’s busiest travel seasons, with shinkansen bullet trains jam-packed and highways congested with cars as urbanites leave the cities en masse to return home. The idea is similar to Thanksgiving or Christmas in some other countries; New Year is when distant relatives try to gather under one roof.

These visits often involve sharing an osechi meal together or a special sake toast to celebrate. It’s also common to pay short visits to neighbors, close friends, or local community members just to exchange New Year greetings (sometimes bearing a small gift, like rice cakes or sweets).

For those who have lost family or cannot travel, the first three days can be a time for phone calls or video calls to exchange New Year wishes. Of course, not everyone has somewhere to go; some families choose to take vacations during New Year’s, as the holiday week is one of the few long breaks in the work calendar. It’s increasingly popular for people to travel domestically, or even go overseas, or to hot springs and ski resorts during the New Year’s period, especially for those who prefer to avoid the hassles of preparation.

Fukubukuro (福袋)

Fukubukuro, or “lucky bags,” are sold by department stores, fashion brands, electronics retailers, and even cafés. These sealed bags contain a selection of items offered at a discounted price (usually 50% or more), with the contents being a surprise.

The tradition dates back to the early 20th century, when department stores began using fukubukuro as a way to attract customers and clear inventory after the year-end rush. Many people line up early on January 1 or 2 to purchase popular bags, especially from well-known brands or limited editions. Today, some stores even release previews or offer online reservations, but the idea of “luck” and surprise remains central to the experience.

How New Year Traditions Are Changing

While many New Year customs remain familiar across Japan, the way families carry them out has gradually changed over time. Japan’s population and household structure have shifted; there are more nuclear families and single-person households now, and fewer multigenerational homes. As a result, some New Year customs have been simplified or adapted, especially in urban areas.

One clear example is mochi making. In the past, it was common for households or local communities to prepare mochi at home through mochitsuki, a labor-intensive process that often involved extended family or neighbors working together. Today, most families buy ready-made mochi from supermarkets or specialty shops, especially in urban areas where space and time are limited. That said, some households, particularly in rural regions, still keep the tradition alive as a yearly ritual.

A similar pattern can be seen across other New Year practices; decorations such as kadomatsu or shimekazari are now frequently purchased pre-made rather than assembled at home, and osechi ryōri is often ordered from department stores, supermarkets, or even convenience stores instead of being prepared over several days. Convenience, smaller household sizes, and changing work schedules have all influenced these shifts.

Likewise, sending nengajō cards is a tradition in decline due to social media and email; younger people may send digital greetings instead of the handwritten postcards their parents used to send.

Family structure and mobility have also affected travel and gatherings. These days, not everyone goes back to their hometown every single year; some alternate which side of the family to visit, and some skip it due to work or other commitments. A recent survey suggested that around 40% of families with children were not planning to travel back home for New Year’s, citing reasons such as the hassle or cost of travel. In such cases, they might celebrate just within their own household in the city.

Despite these changes, it’s important to note that these traditions are evolving, not disappearing, adapting to the pace of modern life while still honoring centuries-old customs. Technology and contemporary lifestyles inevitably influence how things are done. But come December and January, Japan still unmistakably moves to the rhythm of Oshōgatsu: a nationwide pause and an embrace of hope for the future, carried out in millions of homes, each in its own way.

Welcoming the New Year

While specific customs vary by region, household, or generation, the feeling of Japan’s New Year period remains consistent. The first days of January are treated as a pause from regular routines, centered on rest, family time, and practices that mark a clear break from the previous year.

Spending New Year’s Day at home, sharing osechi, visiting shrines, and traveling to see relatives all contribute to this reset before everyday routines resume. Even as some habits adapt to modern lifestyles, these traditions continue to influence how the New Year is experienced across Japan.

🧧 More Than a Visit

Spending time through an internship in Japan gives you the chance to experience these unique cultural traditions as part of your daily life, not only as an observer passing through. If you feel ready to take that step, get in contact with us or join the program so we can help you make this opportunity a reality!